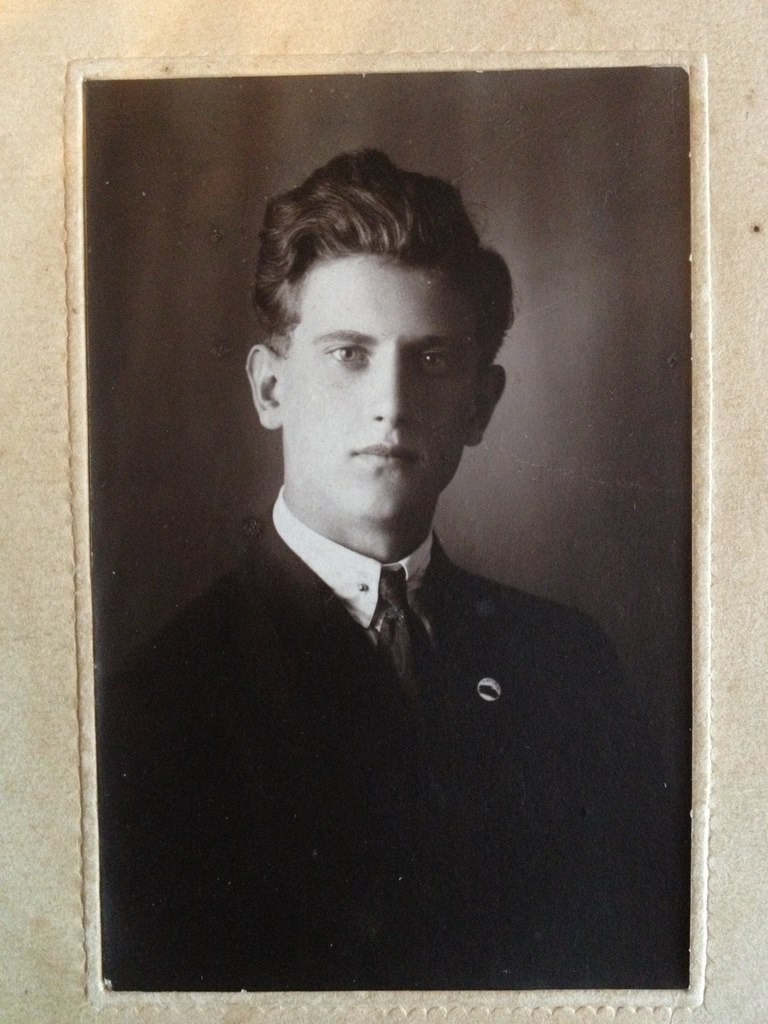

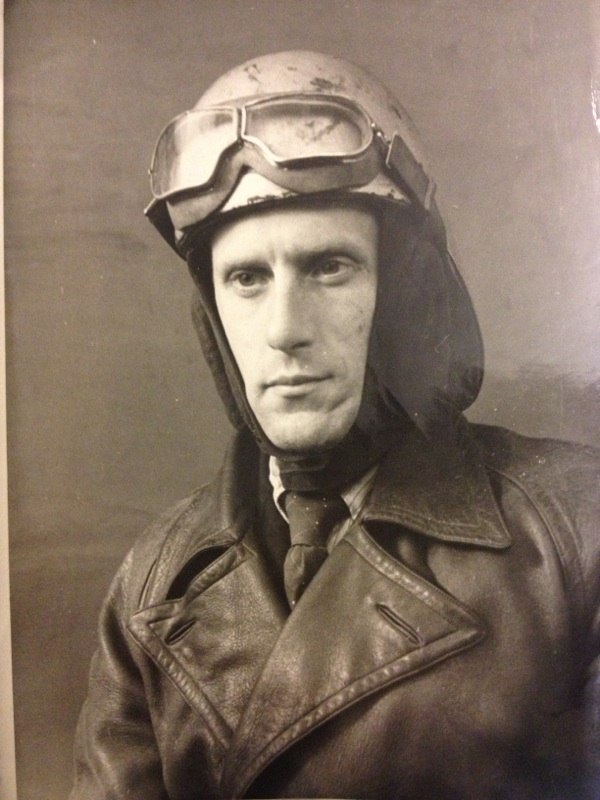

A portrait to remember the legends of sport

Text by Lev Shugurov, oldest moto-auto journalist of Russia

Designers underground movement is a no time event and no country or nationality. And without support of brand firms, equipment and laboratories and sometimes without special education Russian “underground technical specialists” managed to create so perfect machines that brand factories specialists envied but disguised this behind disdainful grin saying “the kitchen…” But the kitchen specialists would ignore this as during record attempts it could have been seen that a talent could not have been substituted with money.

Nikolay Shumilkin, a designer of sports motorcycles, did not come up to this trade occasionally. His father was quite well-known in the south of Russia, a gifted craftsman, he founded a small factory producing small stationary engines, so-called “oils” (these engines worked on petroleum), often bought by well-to-do locals and German colonists, so the engines were named “Kometa” (Comet) that may have been read both in Latin and Cyrillic. The oils proved very reliable and simple in servicing for that time, some of them remained in work till 1950’s.

N. Shumilkin took after his father in love for craftsmanship. As a teenager he built a “motor-sleigh” with Fafnir engine, 1.5 hp. In 1928 this and designer’s name from Rostov-on-Don got a short note in “Za ruliom” magazine (“at steering wheel”). A few years later Shumilkin received a technical passport for motorcycle “Harley-Shumilkin”, which he assembled from parts found on a dump and with a self-made engine.

By that time Shumilkin was already a professional in making chill moulds – forms to cast decorative parts from non ferrous metals. In 1936 he moved from Rostov to Taganrog as there the Taganrog tools plant started production of motorcycles – a whole life occupation of Shumilkin. TIZ-600 based on English prototype BSA, was nicknamed “roe” because of tilted forward cylinder, a reliable and tough design machine with a sidevalve engine was too heavy and unsuitable for races. While nothing of sporting was required from such, as AM (“TIZ AM-600″) stood for “army motorcycle” and 600 – engine capacity.

In 1937 Shumilkin re-designed the engine radically, making a new cylinder with overhead camshaft engine head, decreasing bore from 84 to 77.5 mm, resulting in capacity 495cc in order to fall “under 500cc motorcycles” international category. The engine’s piston he cast from light alloy and cylinder head from aluminum bronze, installed pin springs instead of spiral ones, made “dry casing” oil circulating system with a separate oil tank, left only two top gears in gear box, took off front brake and with some other tricks made the machine lighter. Overhead valves driven by pushing rods, increased compression ratio, megaphone type exhaust pipe, “Amal” type carburetor gave a desired result in power rise from 16.5 to 22 hp and top speed jumped from 95 to 138 km/h.

In 1939 Shumilkin modernized the machine, and named it “TIZ-Kometa-1″. He was first among Soviet designers who got use of a charger and power rose to 30 hp with top speed 157 km/h – an incredible result for those times.

Staff of TIZ plant and Shumilkin relations went for bad and he moved to Leningrad “Red October” motorcycle plant. A re-designed plant’s 350cc model “L-8″ by Shumilkin reached 137kmh at 1km strip with flying start. During the Great patriotic war Shumilkin cast spare parts for aircraft engines in near to front repair workshop. Each “brand piston” had “N.Sh.” label on it.

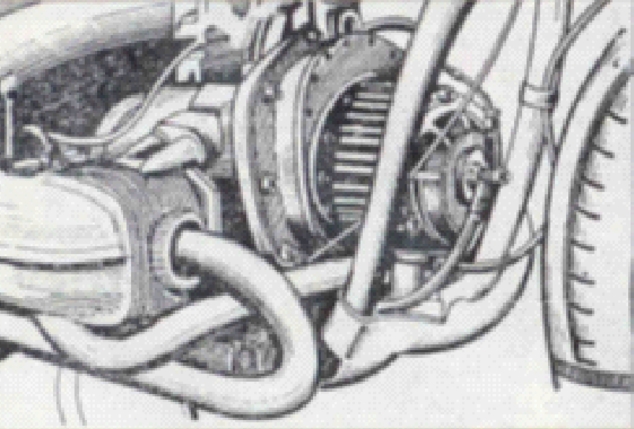

All these years Shumilkin gathered carefully technical information on BMW motorcycles. Unfortunately none of captured racing BMWs got into his hands, though he knew well all weak spots of the German engine. After the war he worked on a new machine “BMW-Kometa-2″, based on BMW R-51, one of the best 500cc motorcycles of that time. Of interest to him were pin springs, short pushing rods of valve mechanism and lower centre of mass of an opposite engine. BMW R51 had two camshafts installed not in cylinder heads but in casing, while short pushing rods were co-axial with valve pushers and did not bend. The designer made new cylinders, valves, pistons were with swollen bottoms that resulted in 7:1 ratio, lubrication system became “dry casing” type with double oil pump and a separate oil tank 3.5 litres capacity, which was a principal solution of cooling a high-tuned engine. Factory’s “general use” racing BMW RS39 were a lightened R51 models with tuned engine without charger, issued for races at low costs and simple design. Unique motorcycles with chargers (only for factory’s racers) had cylinder heads with two camshafts and conical tooth wheel drive for each head.

Such design made in metal was not of opportunity for “a soviet rocket builder” and Shumilkin’s Kometa-2 was equipped with screw charger driven by tooth wheels from front crankshaft end. Change of rotation direction of the charger made carburetor to be placed on left (not on right as factory BMW). Spirit mixture entered carburetor with 25mm diffusing chamber and then the charger pushed the mixture forward to cylinders via rather long ducts, 30mm diameter that also served as receivers (accumulating fuel/air mixture) but the engine was not responsive to throttle.

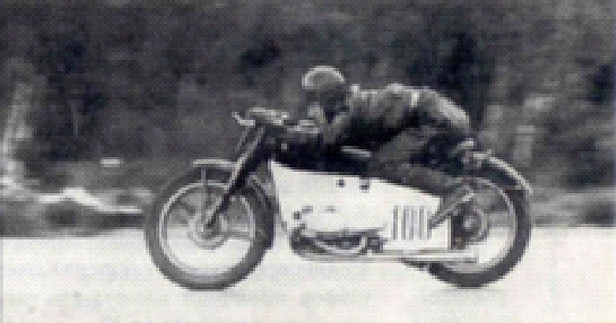

Ignition system had double spark magneto M-48B from a tractor starter and a reducing ratio gear was used for it as Kometa-2 engine raced to 6800-7000 rpm, 1.25 times more than top magneto rotation speed. With 494cc capacity and 0.9 atm (bar) charger pressure power output reached 41hp at 7000 rpm. The machine had no fairing, only a shield under the charger, carburetor and engine casing. Dry weight of the machine dropped to 152 kg wearing 3.50-19″ tires with off-road protector (!) as not other tires could have been found then. During 1946 USSR championship Shumilkin covered 1 km distance with flying start at average speed 169,093 km/h (lower than all-union record that he beat in 1948 with 175,953 km/h). The motorcycle handled on road badly as duplex frame design was not tough enough to provide sufficient torsional stiffness. Designers of racing BMW reinforced frames with two diagonal elements on left and right side under seat, Shumilkin preferred to solve this problem 3,00-21″ wheels with greater gyroscopic momentum. These together with brake drums were borrowed from DKW racing model “URS350”. Rear wheel suspension got friction shock absorbers, the engine was covered with guards and fairing on upper part of the machine.

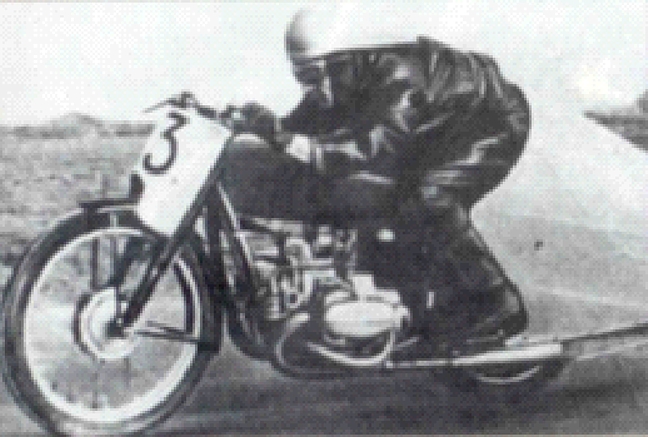

With the same power and transmission ratio, bigger in diameter by 51mm wheels and better aerodynamics resulted in “higher flight speed”. In 1950, Shumilkin not only as a designer but as a racer covered 1 km strip with flying start 184,804 km/h. After that Shumilkin moved from Leningrad to Moscow to work at plant “ATE-2″. The master constantly experimented and tuned engine higher. He researched new mixtures of spirits fuel, increased carburetor diffusing chamber to 27 mm. So in 1946 he used spark plugs with heat rating 280 and by 1950 this increased to 420 with charger’s pressure 1,2 atm engine developed 50-55 hp at 6700-6800 rpm. To avoid overheating and breakage of exhaust valves, Shumilkin machined them filled with natrium (sodium, Na, atomic number 11) inside. A new achievement – absolute speed record of the USSR on 1km strip flying start, 204,894 km/h.

But there were difficulties also – a weak middle web of crankshaft, made with two semi-axes housed in compact design this could not have been made wider 19mm. Endless breakages of cast iron cylinder flange were solved by enforced anchor studs screwed deep into area of crankshaft housing, then aluminum alloy jacket cylinder with press-fitted cast iron sleeve was mounted and alloy head. Tied with nuts such “hamburger” made no trouble anymore.

Then turn came for valves and pistons improvement, intake valves diameter increased to 36mm and the valves made of heat stable steel alloy ZI-69 were not apt to overheating. Again chill-moulded pistons and enforced piston pins. But behind words “made”, “machined”, “installed” lies a vast research work done by an experimenter. Central experimental designers department of racing motorcycles in Serpukhov with N. Gutkin, E. Kulakov were working on the same problems, E.Lorent in Kharkov, J. Stepanov in Rostov, E. Ermanis in Riga, A. Silkin in Moscow were also working on engines for racing motorcycles of 500 and 750 cc categories. Each of them had his own secret and each sought his way.

Next year persistent Shumilkin decreased compression ratio to 6:1, increased charger pressure to 1,4 atm. and got power output 70 hp at 6800-7000rpm. With a tail fairing mounted to his motorcycle he set new all-Union record – 211,765 km/h. Then the racer tested himself in sidecar motoraces with Kometa-2 mounted tube frame, a load and a wheel. Shumilkin set one more all-Union record -179,830 km/h.

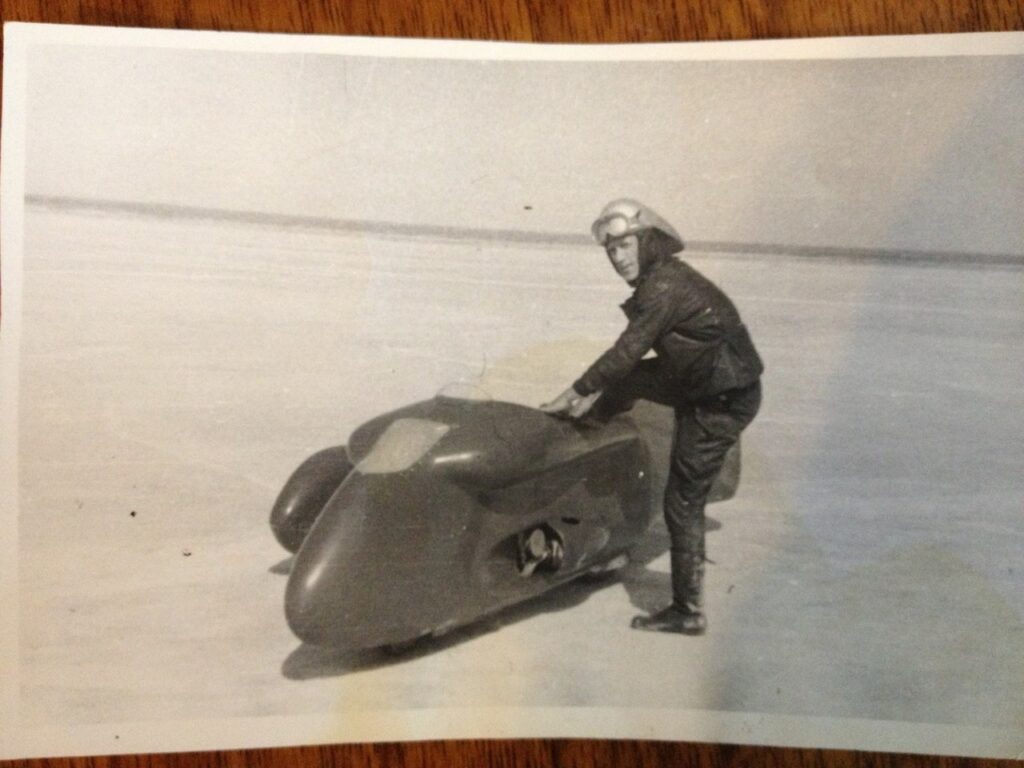

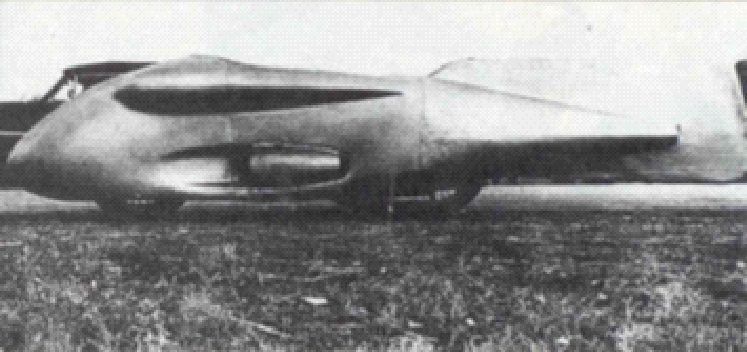

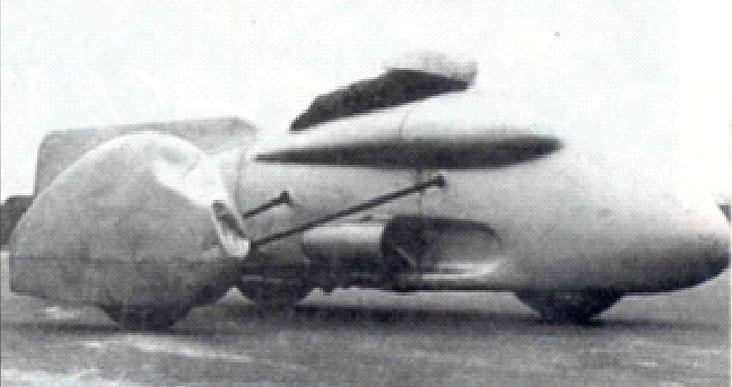

Surprise was that top speed progression stopped. Two specialists from one of aircraft institutes in Moscow came up with idea of full fairing for the motorcycle. In 1.5 years, aluminum fairing designed by B. Blinov and A. Pesochin was mounted onto the machine that had to be welded on different mounts and arms, chassis were changed in design, the frame became longer with wheelbase 1620mm (instead of 1400mm) weight without fairing increased to 170kg. Kometa-3 length (named so after re-designing), was 4100mm, width -800mm, height-989mm. In 1954 “the 3rd” got new charger with same design while with one rotor revolution it supplied not 375cc of fuel mixture but 570cc, 1.5 times more! Methanol was used as fuel charger’s pressure varied from 1,3 to 1,8 atm, engine power was 85-90 hp at 9000 rpm. This all led to 198,019 kmh all-Union record for sidecar for motorcycles in 500cc category. At the end of the year top speed reached 223,663 km/h! 1km strip flying start it made at 134,579 km/h.

Impressed? His last “attack” on his “Kometa-3” N. Shumilkin made in 1958 on 69th kilometer of Moscow-Minsk mainway. 1 km flying start he made at 138,4 km/h, this was his 100th all-Union record.

Soon the legendary mechanic and racer left the motorcycle sport because of age. But unsurpassed “feeling of metal” and great experience led him to a chairman post in one of quiet experimental departments. Shumilkin would look at a broken piece of metal attentively, rotate and test in his hands and then would say his verdict: “here fitting should be loosened, this must not be hardened but normalized, there diamond polishing should be applied…” And that all then worked well! But not without confusions, so when there came a new head of department, he started making his arrangements:” …and that one? Old man, 5 years of school education, file him on pension! Soon the department program began to run down and the head’s post was put to question. Shumilkin was brought back, several years passed and the craftsman was over 70 years of age. He realized that he succeeded in life all he wanted to and could not have done more than that, cocked a trigger of hunting rifle…

Nikolay Shumilkin holds a special post among our “kitchen designers”, he created machines that our well-known motorcycle factories were too way behind him in terms of technical design, achievements and speed records. His name was unfortunately quickly forgotten. Great Jotto’s house in Florence, Italy has a memory table with words: “his name is a long poem”, so name of Nikolay Shumilkin also is a poem about racing motorcycles. Remember this name, the name of a designer blessed by God.

Recollections of Nikolay Shumilkin from a friend

- translated from Russian

this story provided by Vyateslav Kitsis

I figured it out and it turned out that 57 years have passed since the time I first met this person, or rather saw him fly by. I dare to call myself his student only because he himself, then still in the green boys, was happy to introduce himself to his students.

About Nikolay Nikiforovich Shumilkin, I simply had to tell people a long time ago, tell everyone, about a man of amazing sporting destiny. Although human fate also did not bypass him with events that would be enough for several human lives for his eyes to see, and even later a couple of books followed.

I met Shumilkin in 1959, already near the end of his sports career. I was not even twenty at that time. I rumbled around on my 1939 pride and joy BMW R-66 motorcycle, but then the crankshaft had to repaired at the highest level... but who in the Soviet Union could have done this at that distant time? Only such a genius mechanic and technician as Nikolay Shumilkin.

And so in 1959, in an ordinary village house, still left from old Moscow, Shumilkin lived with his wife. How affectionately he was called, the person who set 74 speed records for the country, several of them world records. He fought one-on-one with the then famous NSU company, taking from her from time to time speed records, and at the same time with our “КБ”. That was in Serpukhov, but more on that later.

It takes a long time to tell how I found Shumilkin, this is a whole story, with a detective bias. But when I found him, even me as a young guy with a hint of luxury was struck by the conditions in which this famous and, as often happens with us, undeservedly forgotten man lived.

Nikolay Nikiforovich Shumilkin talked little and rarely about himself, but when it happened, I listened to him with my mouth open and holding my breath. His wife told more, she was bedridden by an incurable illness and on sometimes long evenings, when I waited for Shumilkin at the appointed hour (he had a weakness to completely forget about time), while I was waiting for him I listened to the stories of a woman with traces of former beauty on her face, who forgot about her tormenting pain, she could talk for hours about her "Колушка" ("Kolushka"). She took out his championship ribbons from an old chest of drawers, hung with medals from top to bottom and with difficulty holding its weight with her sore hands, she said sadly: “Nikolay only dresses with it when he is called on big sporting events, just like a general for a wedding, then when the ribbons are removed Shumilkin is forgotten until the next holiday".

Nikolay's most beloved award was confessed by him, the modest badge of the Honored Master of Sports, which he wears proudly without taking off. It is dear to him because his serial number is one of the first in the country.

“It's hard to live next to such an extraordinary person,” I asked her. She thought a little, then laughed and said: “No, only the pillows had to be washed often.” “Why? Surprised me: "And he thought over his glands, hands in his hair, triggers, and they were always in the engine oil and grease ..."

I asked her "How did you happen to be here in this place?" Praskovya Shumilkina very simply, she explained:

“Vasily Stalin, the son of I.V. Stalin, a great lover of technical sports, “ordered” us, the Shumilkin family, to the capital, we even had a warrant for a five-room apartment in a posh house on Begovaya. But, while things were being gathered for our departure, some time passed. Vasily Stalin managed to fall out of favor with his “difficult” father and everything went head over heels. When we arrived in the Moscow, no one even talked to us, thank God that we got such a hut to live in, otherwise his medals would have remained in the open" she joked bitterly.

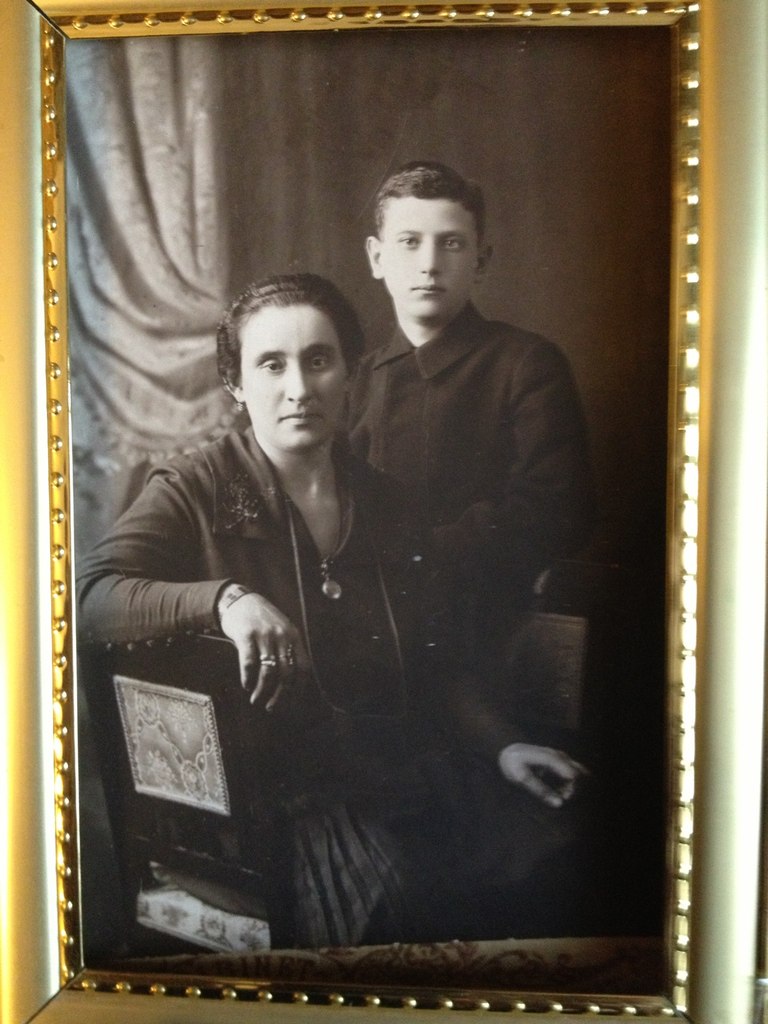

Nikolay Shumilkin was born and raised in the family of a hereditary, foundry master who had his own foundry even before the revolution, known far beyond the borders of a small town. After the revolution and before the war. the Kremlin elite, driving around in imported Rolls-Royles and Hispano-Seuss, began to experience a shortage of spare parts for their expensive cars. Ordering abroad, with the iron curtain, which they themselves hung up, was somehow not with their hands, and they found a way out ... this way was the Shumilkin family.

At the Rostov airfield, the plane from Moscow was patiently waiting for the talented Shumilkin to cast new pistons from the coveted alloy known to him alone. The plane could wait a week, another, as long as necessary, only one thing was required from the master ... not to be mistaken in the alloy recipe, but that the Kremlin did not forgive mistakes. And as long as the Shumilkins were all safe and sound, and young Nikolay successfully mastered the wisdoms of casting, it meant one thing, the family skill was at its best.

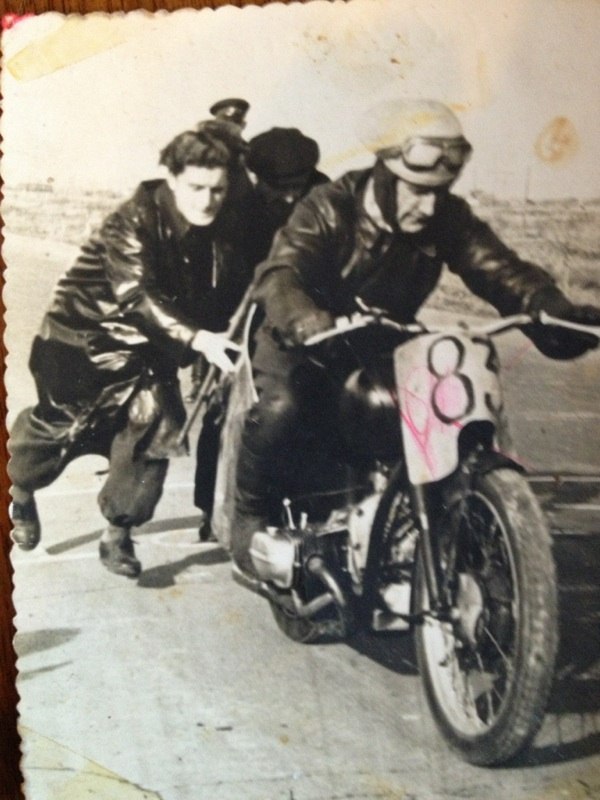

Nikolay Shumilkin won his first victory in the motorcycle field not on the track, but in the same workshops of his father. He was enthusiastic about motorcycles from an early age, but the boy could only dream of them. And so it happened the Chairman of the City Executive Committee was presented with a motorcycle, but not just any one, but a Harley Davidson. Nikolay begged him for a couple of weeks. Since the Shumilkins were not the last people in the city, he succeeded.

The motorcycle was disassembled into "dust", measurements and detailed drawings were taken, then re-assembled and given back to its owner in its original form. A year later, a motorcyclist in a cap pulled over his ears, hiding his violent curly hair, on the saddle of the motorcycle was seen along the narrow, crooked streets of Rostov, and on the crankcase of which cast letters flaunted; "Harley-Shumilkin". Everything in the motorcycle was done by the hands of the young Shumilkin, except perhaps for the rubber on the wheels and the headlight glass with a light bulb.

Then there was motorcycle sport, interrupted by the war, the front, and front-line aircraft repair shops, where an outstanding mechanic and professional foundry worker Shumilkin put an end to the terrible hunger for spare parts. There the combat aircraft stood idle, having developed their flight life, there were no repair pistons. He began to pour pistons for MIGs, Shopkeepers and Petlyakovs from ... pistons of downed and captured German Fokers and Messers. He told this story to me like this, by the way, over a samovar and sipping hot tea, slyly squinting his eyes he suddenly asked: "Do you think that the composition of their pistons was worse than ours? ... here I am of the same opinion."

Before the war itself in 1939, Shumilkin, somehow miraculously, obtained an imported motorcycle magazine. On its cover, the famous German racer Georg Meier was sitting in the saddle of the horizontally-opposed BMW with a compressor. He then won the European Championship on it (there was no world championship yet) and the prestigious T.T. on the Isle of Mann. I saw this cover folded in four, wiped at the seams so that it fell apart in four parts in the hands at the first touch. Nikolay Nikiforovich carried it like an icon through the whole war in his tunic pocket. And after the Victory Day, boxer motors with a Shumilkin compressor sounded on our tracks and records and victories in competitions on the Kometa-2 and Kometa-3 racing motorcycles rained down.

Before the war, Nikolay Shumilkin built his motors on the basis of TIZ600, this motorcycle was called TIZ-Kometa. After the war, all "Komets" were built on the basis of German motorcycles BMW-R 51. The motor, designed for a power of 24hp had to withstand a load of 70 horsepower from a compressor designed by Shumilkin. The turnover was raised from 5500 to 9000. The figures for those times were fantastic.

Nikolai Nikiforovich complained to me: “I tore almost all the crankcases from BMW-R 51 engines that I could find. I realized to put a steel hoop on the crankcase in the flywheel area, similar to those that are worn on barrels. Primitive, but it worked, the crankcase began to withstand a triple load. ” But that was only the beginning. With the compressor, branded pistons constantly burned out. And here the post-war fans of the BMW brand were again left on a starvation diet. Shumilkin exhausted the entire stock of trophy deficit in the country, until he realized it was time to cast his own pistons. As he said: “from my own alloy, which rang like a bell, you just have to hit the pistons with their bottoms a little against each other. I made this bottom of the pistons twice as thick, and with three ribs of rigidity propped up from below, they stopped burning out right away. " The comet acquired a dry sump system and instead of one oil pump in the engine, four appeared. Separately smeared under pressure; the crankshaft, pistons, two camshafts, a compressor and exhaust valves, they could not withstand the heat load, because the engine remained an air vent.

And further. At that time we practically did not have compressor motors on motorcycles, so everything was for the first time. Nobody could tell Nikolay Shumilkin what to do and how, everything was from scratch. He once told me only one case from his rich experience as a designer, it concerned the adjustment of a compressor engine. “Throughout the day of the competition, the engine did not go. That is, of course it goes, but I do not feel the full impact of the motor. It was already getting dark, my assistants were tired and refused to push my “Comet” aside, there was no starter kick for the racing motorcycle and I had to start from the “pusher”. “I myself, already not thinking well, disassemble practically in the dark, for the hundredth time my “Amal” racing corburetor. Well, the guys are pushing me for the last time and you can rest".

"They pushed me and suddenly they threw a TNT block into the engine. When the motorcycle began to drag me from from my handles, I could hardly hang on. I turned around, and on the asphalt there is not just a trace from a rear tire, but just liquid rubber. All who saw this came running up and asked; what's the matter, where does this unexpected power come from? And I myself didn't know what to say. I disassembled the carburetor and what do I see? In this evening bustle, I generally forgot to wrap the jet in the carburetor spray pipe. Well, who could have guessed that the compressor motor needs so much fuel. Not those jets, the opening of which is measured in tenths of a millimeter, but the flow area of a few millimeters!"

In sports, he was called a "sorcerer" behind his back. In those days, all athletes built their own motorcycles. But somehow it was viciously accepted to prepare motorcycles for the start at the last moment. And the riders who had not slept enough, all night sawing something, adjusting and debugging, in the morning at the start saw Shumilkin's “Comet” neatly covered with a blanket, ready for battle.

And so it was every time, and every time, the “Comet” won. The matter reached the point of absurdity. Shumilkin competed not only with amateurs (in Soviet times, there were not yet professional motorcyclists, every time he smashed racing motorcycles produced by "КБ" on the tracks. In Serpukhov a whole design bureau with huge production could do nothing with the “sorcerer” Shumilkin.

And then one day a condition was thrown before the talented designer and mechanic: Either, he gives his Kometa motor to Serpukhov for detailed acquaintance, or he will not be allowed to start. Then he told me: “There is nothing to do, the times were like that. I gave the motor as if I tore it off my heart. Six months later, they returned it, in a sack, and couldn't even put it back together!”. And with a sly smile he added: “I assembled my motor, well, something else “sank” in it, of course, and in the spring I again “smoked ” everyone and this bureau Serpukhov, at the same time.

Nikolay Shumilkin introduced me to a motor and chassis designed for record-breaking 500 cc races with a sidecar, this was the last version of his Comet-3. On the record track of the dried lake Baskunchak, Comet-3 showed an average speed of 237 km / h (races are held in both directions segments).

The starts were unsuccessful. A strong wind was blowing and we had to wait a long time until it was quieter, otherwise it simply blew the “Comet” off the track. The motorcycle was in a fairing, with a large stabilizer resembling the tail of an airplane and in one of the successful attempts, a side wind blew so that it seemed the motorcycle was about to hit the gate, where the timekeepers were standing. This impressed the judges so much that they threw away their instruments and scattered. With a desperate effort, Shumilkin still hit the target with a record speed, but there was no one to confirm it.

There was a re-run, but the clutch began to fail and the record did not work, it was not possible to overcome the 240 km/h line. These figures, which then seemed cosmic, were beyond reality for me. My BMW R-66, which was considered the fastest motorcycle in Moscow in that 1959, accelerated to 150 km / h.

Now many years later. Nikolay Shumilkin has not been with us for a long time and sometimes it is a shame to tears, because life becomes insanely interesting, especially when it comes to motorcycles, but life is so unfairly fleeting. He was always sincerely delighted when he saw something new in motor vehicles. And if he would live to this day, when anyone, I emphasize anyone, can go to a motorcycle dealership and buy a motorcycle for himself, which will easily exceed the record of his famous “Comet”…. I can see directly ... how, according to his custom, running his hand soiled with machine oil into his thick, graying, curly hair, he would be happy about it like a child, believe me, more than all of us put together.

author: Vyacheslav KITSIS

Additional sources:

moto oppozit

© Translation by Evgeny Radchenko specially for b-cozz.com

top